At the risk of stating the obvious, our brains enable everything we do. However, they also get in the way and occasionally prevent us from accomplishing our goals.

The same brain that helps us communicate a message that truly resonates with an audience is the one that prevents us from communicating effectively at other times.

Have you ever wondered how those things are all true at different moments?

I can’t explain all the reasons, but I’d like to describe a framework that has helped me understand more about myself and the ways that I interact with the people around me.

The SCARF model was defined by David Rock in his marvelous book, Your Brain at Work. SCARF focuses on five ways that our brains respond to the world around us, and more particularly, to the people with whom we interact.

One of Rock’s key messages is that a comment or situation that affects one of the five SCARF elements triggers the same response in the brain as a physical stimulus. For example, the feelings of warmth and contentment from an unexpected compliment are neurologically similar to the pleasure that results when you’re hugged by a loved one. And disappointment from having your suggestion dismissed in a meeting is no different to your brain than the embarrassment of tripping and falling in front of an audience.

To our brains, social pain is virtually identical to physical pain, consequently, it behooves us to act in ways that provide rewards not threats to the people around us.

Let’s examine the five components –

Status,

Certainty,

Autonomy,

Relatedness, and

Fairness – that are woven into the SCARF each of us wears.

tatus

Your brain is continually assessing your status compared to people you encounter. Sometimes we make these assessments consciously, but most of the time it happens without conscious thought.

“Am I more important than Steve?”

“Do I need to defer to Jane?”

“How does the work I’ve done measure up to my colleagues?”

Recognizing that this is going in your head and everyone else’s can help focus your attention on boosting the status of those around you. Be the person who compliments and thanks others. Don’t be the person who constantly interjects or tries to “one-up” other people in the room.

Addressing Status

Increased by:

- Getting promoted

- Receiving a “pat on the back,” especially in public

- Being paid a compliment, especially if it’s unexpected

Decreased by:

- Losing an argument

- Being wrong in public

- Having someone say “Can I give you some feedback?”

ertainty

Your brain craves certainty! While some people relish trying new things or enjoy surprises, at some level we all like knowing what’s going to happen: There is comfort in knowing that the sun will rise and set, and that the tide will come in twice every day.

We search for familiarity and look for things we recognize. But if we can’t have certainty, making a good guess can be a reasonable substitute.

Addressing CERTAINTY

- Predictable actions from colleagues

- Setting and meeting a goal

- People doing what they say they’ll do

- Walking into a room full of strangers

- Starting a new job

- Arbitrary changes in rules or operating instructions

utonomy

Your brain wants to be in charge or be able to make choices.

Keep this in mind when you’re leading a group or managing a project. Realize that people need some measure of control to satisfy their need for autonomy. It’s true, of course, that everyone can’t be the project manager at the same time, but look for ways to ensure each person can be empowered. Don’t be an authoritarian—let others participate in setting guidelines and making decisions.

Addressing AUTONOMY

- Taking responsibility

- Being empowered to make decisions

- Feeling in control

- Being micromanaged

- Needing multiple signoffs

- Being forced to change

elatedness

One of the most powerful human needs is the need to belong; we all want to be part of something.

Our brains seek out ways to be part of a team, a member of the circle, or even part of the inner circle. To borrow a phrase from Lin-Manuel Miranda and Hamilton, we want to be in the room where it happens.

Complicating our sense of relatedness is the fact that our brains automatically classify people as friend or foe – and the default is foe! Although these designations are based on the millennia-old wiring in our brains, stemming from a time when “friend” or “foe” could be a matter of life or death, the unconscious categorization still happens today.

One of my favorite bits of advice along these lines is this: When talking to a group of people at a conference or in a hallway, don’t stand in a circle. Stand in a U-shape or leave a gap in the circle; the implicit invitation conveys a powerful message.

Addressing RELATEDNESS

- Being asked to join

- Being part of a team

- A hug from a loved one

- Removal from a team or a project

- Rejection

- Foe-like behavior from a friend

airness

Equal treatment and fairness trigger positive responses in our brains.

In your daily interactions, do your best to exhibit the same behavior toward everyone. Not only will that help others feel a sense of belonging, but you’ll be modeling fairness, inclusion, and equity for those around you.

Addressing FAIRNESS

- Appropriate treatment in public

- Being trusted

- Participating in or being informed why decisions were made

- Being cheated

- Discovering unequal pay or biased treatment

- Betrayal, especially by someone close to you

Summary

As you’ve read my description of SCARF, I hope you’ve had the same realization I did when I first read David Rock’s book. Though the title of the book is Your Brain at Work, everything I’ve described about the SCARF model applies equally to the people in our personal lives. Consequently, I’ve tried to apply these principles to the members of my family and to my friends.

I’d like to reiterate a foundational principle of SCARF that I mentioned earlier: social actions and cues produce nearly identical results in our brains as physical actions. To say that another way, the words we speak, our body language, and the gestures we make can trigger release of adrenaline (threat!) or dopamine (reward!), producing the same neurological results as physical stimuli.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the SCARF model is only a small part of Your Brain at Work – there is so much more to learn about our brains from Rock’s book. The good news is that this is one of the easiest-to-read books about neuroscience topics that you’ll ever find, partly because of its storytelling format.

Rock built the book around a fictional couple and their two children. Each chapter opens with a story centered on one of the adults and describes a situation that doesn’t go as well as he or she would like. Next, Rock explains a neuroscience principle or two, then re-tells the story as the central figure draws on neuro knowledge and produces a better result.

The human brain is a remarkable thing! I hope the SCARF model has convinced you that knowing more about how our brains operate can help us work and live together more effectively.

– Scott

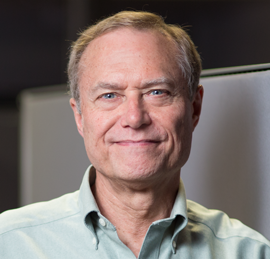

Scott Helmers

Sr. Instructor

Scott A. Helmers is a Partner at the Harvard Computing Group, a software and consulting firm that assists clients with understanding and implementing business process solutions. He is a co-inventor of TaskMap, a Visio add-in that allows anyone to document, analyze, and improve their business processes. Scott has worked with clients in ten countries on projects involving process mapping and redesign, knowledge management, and technology training.

Scott has been named Microsoft Valuable Professional (MVP) for Visio every year since 2008, one of only six people in the world to hold that distinction. He is a course author for LinkedIn Learning, a Senior Instructor with B2T Training, and is the author of four books from Microsoft Press, including Visio 2016 Step by Step.